© 2010-2021 by Fine Arts of the Southwest, Inc. All rights reserved.

Unauthorized reproduction or use is strictly prohibited by law.

A rare and remarkable historic New Mexican tinwork, glass and wallpaper nicho by Jose Maria Apodaca, c.1890-1910

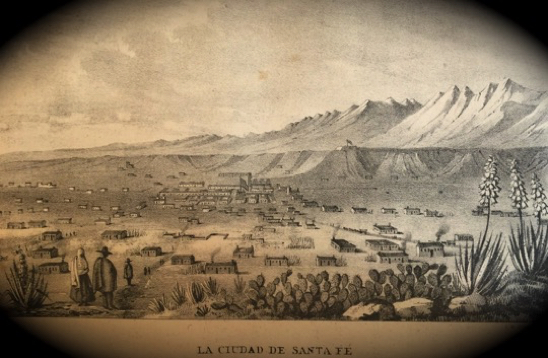

Artistic greatness often emerges from the most humble of origins, places and circumstances and none more so than in the case of the historic New Mexico tinworks of 1860-1920. They are a very early example of the modern term “recycling” in that they originally began their lives in a very different form, that of commercially manufactured common tin cans. These tin cans of various sizes, originally containing lard, coffee, vegetables, flour and other substances were originally brought into New Mexico by wagon trains traveling overland to Santa Fe along the old Santa Fe Trail from St. Louis Missouri, a trail which first opened in 1821 and just celebrated its 200th anniversary.

The 870-mile-long Santa Fe Trail was established to take advantage of new trade opportunities with the nascent new Republic of Mexico, which had recently won its independence from Spain in 1821 in the Mexican War of Independence. The trail was used to haul manufactured goods, people and livestock from Missouri to Santa Fe, which was then in the northern Mexican state of Nuevo Mexico. The Old Santa Fe Trail served for the next six decades as the critical primary commercial highway for the flow of goods from the east arriving into New Mexico until the railroad reached the outskirts of Santa Fe in 1880.

The new ready availability of commercial tin metal made for a critical development in the long history of New Mexico devotional artwork. Up until the last half of the 19th century, New Mexican religious retablos and nichos had always been typically and traditionally crafted from boards of painstakingly cut and hand-adzed local Ponderosa pine wood which were then carefully carved, gessoed and painted with the images of various saints and other religious tableaus. Now retablos and nichos could be made more quickly and inexpensively with the easy and widespread availability of completely commercial, mostly salvaged materials now at hand; used empty tin cans, discarded panes of window glass, unused wallpaper fragments and commercially produced printed religious images.

To make a tinwork “retablo” or a “nicho” a tinsmith would first secure a suitable quantity of salvaged commercial tin lard or other cans which would then be cut, shaped, fashioned, stamped, soldered, decorated and occasionally painted and ornamented in various ways and with various materials such as colored and patterned pieces of salvaged wallpaper or paper flowers to make the desired size and form of the tin frame. The tinsmith would set the tin frame or nicho with the desired paper religious print or with an arrangement of multiple prints or small Holy Cards or fancy colored chromolithographs many of which were often obtained directly from local Catholic priests often at the Church itself. In addition to tin retablos and nichos, other forms of New Mexico tinwork commonly made during this time period were wall sconces, candlesticks, candelabra, hanging fixtures and processional pieces as well as various small tin attributes, such as crowns made for accenting carved wooden bultos and santos.

As was most likely in the case of this particular nicho, many historic New Mexico tinwork pieces were made to a specific order and purpose for a particular individual, private family or small religious organization such as a Penitente Morada or local village chapel. It is likely that in the case of this particular piece, which is larger, fancier, more significant and costly piece, the order might have come from a religious organization such as a Penitente morada or village chapel or possibly from a commercial trading post in the area which we will discuss in more detail later.

The tin nicho measures an impressively-sized 14 1/2” in height and it is 9” in width and 3 1/2” in depth. It is composed of fifteen tin, glass and wallpaper panels, all surrounding a large central tin and glass box which contains a beautiful and expressive period, c. 1900 New Mexico carved wooden bulto, 6” in height, made by renowned New Mexico Santero Jose Benito Ortega (1858-1941) or by one of his followers or apprecntices. The small wooden bulto is suspended in the nicho by being wired onto the back panel of the nicho with a length of old steel wire. The back panel of the nicho is most beautifully and elaborately decorated with complex stampwork designs which accentuate and highlight the wooden bulto perfectly. It is very possible that the family or religious organization or company which commissioned this nicho from Apodaca also gave him this bulto and asked him to make this nicho to house it. Overall this carefully conceived and assembled highly complex piece is a beautiful, expressive, harmonious and artistic composition and assemblage overall, perfectly characteristic and evocative of Apodaca’s exalted artistic sensibility and unique technical virtuosity.

The talented artist who made this distinctive piece is readily identifiable as Jose Maria Apodaca (1844-1924) as can be ascertained by numerous certain telltale characteristics of the work itself, notably its overall design layout and general appearance, the specific square profile flat formation of the tin channels, the design of the tin corners, the stamp worked designs on them and the intentionally elaborate and artistic use of multiple tin and glass panels containing fancy colored wallpapers. Apodaca lived most of his life in the remote tiny one-horse village of Ojo de la Vaca which translates to “Eye of the Cow” located about 20 miles as the crow flies to the southeast of Santa Fe. Local area people knew him as a “hojatalero” or ‘tinsmith’ and they came to him with commissions and orders. Apodaca also traveled regularly in his horse or mule-drawn workshop wagon around the local area and even further afield with his tools and materials soliciting work and made tinworks for people in other New Mexico villages and towns possibly even traveling as far north as some of the small Hispanic border communities of southern Colorado such as Antonito, San Luis and La Jara.

Jose Maria Apodaca is generally considered to be the finest and most accomplished of all known historic New Mexico tinsmiths with the possible exception of his contemporary, Higinio V. Gonzales (1842-1921), who also made a variety of beautiful, high-quality work. Apodaca’s pieces, particularly his later 1890-1910 works such as this nicho, are certainly among the most complex and elaborately and well-crafted New Mexico tinworks often using multiple tin, glass and wallpaper panels and elaborate scalloping, painting and other added fancy decorative touches.

View of the ruined church in the now-mostly

abandoned village of Ojo de la Vaca, NM

Historic etching of the city of Santa Fe, the end of The Old Santa Fe Trail, c. 1848

“Fate and good fortune has preserved a substantial body of Jose Maria Apodaca’s work,

preserving it for posterity so that it may be appreciated by successive generations of New Mexicans

and collectors who have the good sense to value the contributions of those who came before. As long as there are those individuals who appreciate beauty, the Ojo de la Baca tinsmith’s artistry will endure.”

—New Mexico tinwork authority and scholar, Maurice M. Dixon, Jr.

Excerpt from an essay © 2012 by Maurice M. Dixon, Jr. All rights reserved. Published by permission.

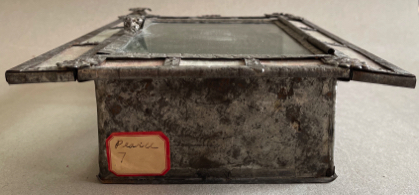

A fragment tin lard pail dating from 1885-1902 of the type used to make this nicho excavated from an archeological site near Ft. Wingate, New Mexico.

Photo courtesy of and © by Jay Willian, 2017. All rights reserved.

The Hotel Castaneda in Las Vegas, New Mexico pictured in a 1906 Fred Harvey postcard.

It is completely possible that this nicho passed through one or both of these establishments at some point in its life. After all, Jose Maria Apodaca lived only a mere 60 miles from Las Vegas, New Mexico and the Hotel Castaneda and he passed through there regularly on his various excursions and he very likely also had clients in the immediate area. In 1899 when the Casteneda was built Las Vegas, not Santa Fe was still the commercial hub of northern New Mexico. Apodaca could easily have sold the nicho to (or made it on a special order for) the Harvey Company personally. The paper label is inscribed with the name “Pearce” in an old-fashioned hand in black India ink which is seemingly the name of a previous owner or perhaps the person the Harvey Company might possibly have commissioned Apodaca to make it for.

This nicho is an exceptionally beautiful, extremely rare and highly-refined historic devotional New Mexican artwork almost miraculously created from the humblest of salvaged scrap materials by an inspired and brilliant New Mexico folk artist,

a piece which perfectly reflects the time, place, faith and unique geographic and historic circumstances of its creation but which also projects a completely timeless and lasting universal artistic beauty, humanity and devotional spirit.

SOLD

Jose Maria Apodaca at center (1844-1924)

Photo source and © “New Mexican Tinwork, 1840-1940” by Lane Coulter and Maurice Dixon Jr., UNM Press Albuquerque, 1990

The nicho is in remarkably excellent original condition and particularly so considering its 130 or so years of age and the remote rugged frontier region in which it was born and spent much of its life. There are no cracks at all to any of the many glass panels and none of them appear to have been replaced. This is somewhat unusual for a New Mexico tinwork of this age, complexity and large size and it indicates the very strong likelihood that the piece was unusually well-cared for over the years of its life and/or that it possibly hung undisturbed for a long time period in a specific religious building or family home. One of the original tin hanging hooks has become slightly separated from the rear wall of the nicho and thus we suggest that it either be displayed sitting on a table or shelf or that its fortunate purchaser have a wall mount made to hold it if a wall display is desired.

There is another quite fascinating additional element to this nicho’s story and that is a clear indication of the presence of one of the most remarkable and desirable historic commercial provenances in the American Southwest; that of the famed Fred Harvey Company as evidenced by the large red-bordered octagonally shaped white paper label prominently affixed to the underside of the nicho. The Fred Harvey Company had these distinctive labels specially custom made for them in various sizes and affixed them to virtually every piece of art sold at the company’s extensive network of trading posts across the region. The Fred Harvey Company sold a wide variety of the finest Southwestern arts and crafts in existence, from Native American weavings, pottery, jewelry and basketry to Hispanic wooden bultos and retablos to tinwork and textiles at its various trading posts around the Southwest including The Indian Building Trading Post at the famous Hotel Alvarado in Albuquerque, New Mexico and the equally famous Castaneda Hotel in Las Vegas, New Mexico.